The Art of the Tattoo

By: Geoff Ostling (Sep 19 2022) They have been worn by kings and convicts. The ‘iceman’ who lived in approximately 3300 BC had 57 of them. The ancient Celts had them. They were so heavily tattooed that their enemies thought they wore blue paint – called ‘woad’. The body of King Harold of England was identified after the Battle of Hastings in the year 1066 from the tattoos he wore on his chest and the name of his queen tattooed over his heart.

They have been worn by kings and convicts. The ‘iceman’ who lived in approximately 3300 BC had 57 of them. The ancient Celts had them. They were so heavily tattooed that their enemies thought they wore blue paint – called ‘woad’. The body of King Harold of England was identified after the Battle of Hastings in the year 1066 from the tattoos he wore on his chest and the name of his queen tattooed over his heart.

Over the last two centuries in Europe, the United States and Australia, tattoos have been in fashion, and out of fashion. They have been loved and hated. The art of the tattoo has flourished in both wartime and peacetime, and now at the end of the twentieth century tattoos are very much back in fashion. Just look at coffee table books of photographs of tattoos or the half dozen or so different tattoo magazines available in any newsagent in Australia, or the arms, chests and legs of musicians on television.

One of Australia’s richest young men, Lachlan Murdoch has a tribal band tattooed around his left forearm just below the elbow which is regularly seen whenever he rolls up his shirt sleeves and a rock lizard on his right biceps. Princess Margaret is believed to have a tattoo on her bum.

One of Australia’s richest young men, Lachlan Murdoch has a tribal band tattooed around his left forearm just below the elbow which is regularly seen whenever he rolls up his shirt sleeves and a rock lizard on his right biceps. Princess Margaret is believed to have a tattoo on her bum.

What is it that makes people mark their bodies so permanently? Why do they do it?Probably most men have thought about getting a tattoo at least once or twice in their lives. What is the fascination with this ‘living art’? And if you are going to get a tattoo, how should you go about it?

On 28 March 1998, Geoff Ostling spoke to a large group of MAG members about the history of the tattoo. It was Captain Cook and Sir Joseph Banks who popularized them in England in the late eighteenth century after their journey to the South Seas, which included the European discovery of New Zealand and the East Coast of Australia. The heavily tattooed Polynesian warriors met on this expedition started a new craze in tattoos and everybody wanted one.

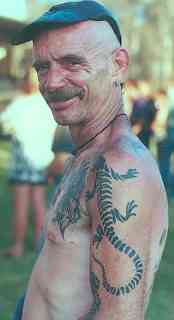

The two eldest sons of Queen Victoria got large oriental dragons tattooed on their arms as souvenirs when they visited Japan.Sir Winston Churchill’s mother had a delicate serpent tattooed around her wrist. The last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, who was murdered with his wife and children by the Bolsheviks in 1917, was heavily tattooed, as was his cousin, King George V of England and many members of the European aristocracy

The two eldest sons of Queen Victoria got large oriental dragons tattooed on their arms as souvenirs when they visited Japan.Sir Winston Churchill’s mother had a delicate serpent tattooed around her wrist. The last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, who was murdered with his wife and children by the Bolsheviks in 1917, was heavily tattooed, as was his cousin, King George V of England and many members of the European aristocracy

Tattoos have been, and continue to be, the ‘mark’ of the sailor. When there was little or no wind to fill the sails, sailors on long voyages occupied themselves with scrimshaw, the art of carving pictures on whale teeth or ivory. They also tattooed these pictures on each other, often using a needle for repairing the sails and soot or gunpowder mixed with rum or saliva for ink.

Sometimes a gifted sailor-artist would carry his needles, genuine India ink, and a selection of hand-drawn designs in a small box, and then when his sailing days were over, set up shop in a seaport or outside a military establishment and continue tattooing. And so the tradition continues today. When navy ships dock at Garden Island, and the sailors get leave, they head for Kings Cross, for girls (or boys), grog and a new tattoo from one or other of the three tattoo studios situated on, or just off, Darlinghurst Road.

Sometimes a gifted sailor-artist would carry his needles, genuine India ink, and a selection of hand-drawn designs in a small box, and then when his sailing days were over, set up shop in a seaport or outside a military establishment and continue tattooing. And so the tradition continues today. When navy ships dock at Garden Island, and the sailors get leave, they head for Kings Cross, for girls (or boys), grog and a new tattoo from one or other of the three tattoo studios situated on, or just off, Darlinghurst Road.

Many of the convicts transported to Australia arrived wearing fresh tattoos. Convict records at the Barracks Museum in Sydney mention initials of loved ones, dates, slogans or memories of home. It has been seriously suggested that the antagonism towards tattoos that exists in certain circles in Australia comes from the fact that tattoos represented a convict past that the cream of Australian society would prefer to forget.

Tattooing is still practiced in jails across the world, usually with tattoo machines made from the tube of a ballpoint pen and a motor from a transistor radio. Conditions for prison tattooing are usually far from hygienic. But in a prison situation, tattoos are the one possession that cannot be confiscated. They are the one thing that is permanent. They confirm that the person is an individual. Tattoos remain till death.

Tattooing is still practiced in jails across the world, usually with tattoo machines made from the tube of a ballpoint pen and a motor from a transistor radio. Conditions for prison tattooing are usually far from hygienic. But in a prison situation, tattoos are the one possession that cannot be confiscated. They are the one thing that is permanent. They confirm that the person is an individual. Tattoos remain till death.

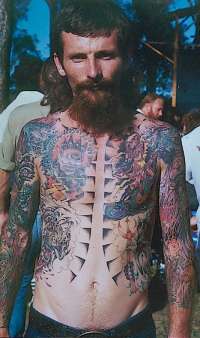

It used to be said that if you didn’t get your first tattoo by the time you turned 25, then you would never get a tattoo. That has changed these days with many older men fulfilling a desire they have had for many years and getting some permanent artwork. It must be said that tattooing can be addictive and most men cannot just stop at one. Some continue to get more and more ink until they have a full body suit while others get what is called in the tattoo industry ‘needle-shy’. They just stop visiting their tattoo artist for no apparent reason, sometimes with major artwork on their back or chest left incomplete.

Why do people get a tattoo? What makes us do it? And why are tattoos so popular in the gay community?

Why do people get a tattoo? What makes us do it? And why are tattoos so popular in the gay community?

In his book, Bad Boys and Tough Tattoos, Sam Steward, a gay American tattoo artist has listed at least 15 reasons for getting ink under the skin. Using slides taken at the 1998 Sydney Tattoo Show on the same day as the Mardi Gras parade, Geoff endeavoured to show examples of all 15. Of course for many men, it is mixture of several of these motivations.

The first is possession. To show where or to whom you belong and where your allegiances lie. A ‘Property of (name)’ tattoo on an arse cheek is a permanent sign of what you hope will be, but which might not be, a life-long relationship. There is an old saying in the tattoo world that ‘tattoos last longer than marriage’.

The first is possession. To show where or to whom you belong and where your allegiances lie. A ‘Property of (name)’ tattoo on an arse cheek is a permanent sign of what you hope will be, but which might not be, a life-long relationship. There is an old saying in the tattoo world that ‘tattoos last longer than marriage’.

A tattoo may be the symbol of belonging to a group, such as joining a teenage gang, or joining one of the services. Sometimes it is herd instinct. ‘Everyone else in the gang has at least one tattoo and I want one too.’ The name of the group will be tattooed across the chest or often these days, in large black Gothic script in a fan shape just above the navel.

For some men getting a tattoo is a manhood initiation rite. It shows: ‘I’m grown up. I’m tough. Piss off, Mum and Dad, I’m no longer Mummy’s little boy. I’m now a man and can bear the pain of getting a tattoo. No one can tell me what I can or cannot do any more.’

For some men getting a tattoo is a manhood initiation rite. It shows: ‘I’m grown up. I’m tough. Piss off, Mum and Dad, I’m no longer Mummy’s little boy. I’m now a man and can bear the pain of getting a tattoo. No one can tell me what I can or cannot do any more.’

It may also be a mark of a changed life, the outward symbol of coming out as a gay man, or of conquering an addiction. Nailing your flag to the mast, so to speak, for the entire world to see, with the knowledge that ‘there is no going back’ into the closet, or back to the slavery of that particular addiction. These sorts of tattoos may celebrate a marriage or (more commonly) a divorce, the birth of a first child, or retirement from a stifling office job and the symbol of a new life of freedom.

Then there is sentimentality. A tattoo can be the living memorial to a loved one, be it parents, children or partner. The typical sentimental tattoo is a heart or cross with a scroll, often surrounded by red roses and a name. Sometimes you see the words ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’ and this is because the young man getting the tattoo is not sure which parent will be more angry, so he decides to placate them both.

This is related to tattoos showing national or ethnic origins. It is not unusual to see youngsters with symbols of Australia such as the flag with kangaroos, emus or native birds just like the tattoos their great grandfathers and grandfathers got before setting off for Gallipoli in 1915 or for the jungles of New Guinea during World War II. There are also tattoos which relate to religion, consecration and even stigmata Christ’s head with a bloody crown of thorns, Christ on the cross or the ‘Rock of Ages’. For others, magic or totemism will be the motivation, Words in Sanskrit or other ancient languages, Buddhist symbols and esoteric images all find their way onto the bodies of some young people.

This is related to tattoos showing national or ethnic origins. It is not unusual to see youngsters with symbols of Australia such as the flag with kangaroos, emus or native birds just like the tattoos their great grandfathers and grandfathers got before setting off for Gallipoli in 1915 or for the jungles of New Guinea during World War II. There are also tattoos which relate to religion, consecration and even stigmata Christ’s head with a bloody crown of thorns, Christ on the cross or the ‘Rock of Ages’. For others, magic or totemism will be the motivation, Words in Sanskrit or other ancient languages, Buddhist symbols and esoteric images all find their way onto the bodies of some young people.

For some men the motivation is sado-masochism – they glory in the pain and will often tell you how much a particular piece of artwork hurt, sometimes years after they got the tattoo. While on the subject of pain, yes tattoos do hurt. If tattoos came out of cornflakes packets then no one would want them.. They are valuable because they do hurt. On the other hand, if the pain were unbearable, then no one would ever get a tattoo.

Tattoos can also be a form of advertisement. Guys who are into various forms of bondage or S and M will have particular symbols tattooed on them. Troughman of Mardi Gras and Sleaze Ball fame has a tattoo of a large yellow pig lying in a pool of urine with the word ‘Troughman’ in elegant computer style lettering under the picture.Some men have the letters LTFC and ESUK on the knuckles of their hands which turn into the words ‘LETS FUCK’ when the fingers are intertwined. One young man at the Sydney Tattoo Show said he told his mum that the letters ESUK and LTFC, newly tattooed on his fingers, was his girlfriend’s name – in Lebanese!!

Tattoos can also be a form of advertisement. Guys who are into various forms of bondage or S and M will have particular symbols tattooed on them. Troughman of Mardi Gras and Sleaze Ball fame has a tattoo of a large yellow pig lying in a pool of urine with the word ‘Troughman’ in elegant computer style lettering under the picture.Some men have the letters LTFC and ESUK on the knuckles of their hands which turn into the words ‘LETS FUCK’ when the fingers are intertwined. One young man at the Sydney Tattoo Show said he told his mum that the letters ESUK and LTFC, newly tattooed on his fingers, was his girlfriend’s name – in Lebanese!!

This is related to the next motivation for getting a tattoo – non-conformity and rebellion. ‘Fuck the rest of you, I’m me and this is the way I am’. For some guys, tattoos are a form of exhibitionism and so they get tattooed on their forearms, their hands and fingers, their neck, the top of their head or face where they have to be noticed. They can’t be missed. These tattoos are a statement

The final motivation is pure decoration. Tattoos can be extremely beautiful – and masculine – and sexy. We like the way the way tattoos look on other men and we want that look too. Geoff’s talk ended with half a dozen men in the audience showing their tattoos and briefly describing where and why they got them and why they chose their particular design.

The final motivation is pure decoration. Tattoos can be extremely beautiful – and masculine – and sexy. We like the way the way tattoos look on other men and we want that look too. Geoff’s talk ended with half a dozen men in the audience showing their tattoos and briefly describing where and why they got them and why they chose their particular design.

Marked Men is a club for gay tattoo fans, which meets regularly in Sydney at the Barracks Bar at Taylor Square. There is an illustrated newsletter every two months and there are Marked Men members in all states of Australia and in Europe and the United States. The club is a non-profit organisation and the annual subscription of $10 pays for the cost of printing and postage. Ring Geoff or Joe at (02) 9568 3029 for more information.

The Tattoo Exhibition, which traces the history of tattooing through the Pacific, in Japan and in Australia, is at the Justice and Police Museum (in the beautifully restored Water Police Court House, just near Circular Quay railway station). The exhibition contains some 14 of Geoff’s photographs of tattoos and part of his collection of books and pictures of tattoos. The museum is open every weekend and the Tattoo exhibition will continue until November 1998 when it will go on tour to other cities. It is by far the most successful exhibition ever staged by the Historic Houses Trust.